Norman Franke – 21 January, 2024

Their joint presentation includes Vea's installation of a typical farm labourers' smoko. On display are cheap plastic chairs, a large plastic dining table, a microwave and a fridge on whose door there is a handwritten list of the telephone country codes of Samoa, Tonga, Vanuatu, Fiji and other Pacific regions from where the majority of New Zealand's seasonal labourers originate. The installation recreates a feel of desolation and homesickness but also of subtle camaraderie and solidarity, as the table, although simple, is large and capable of holding a communal meal and a game of cards.

Auckland

Jasmine Togo-Brisby and John Vea

Outcast

Curated by Lisa Beauchamp

Essay by Ioana Gordon-Smith

20 October 2023 - 27 January 2024

Let’s begin by looking at the Employments Relations Act 69DZ where “an employee is entitled to, and the employer must provide the employee with, rest breaks and meal breaks […] If an employee’s work period is more than 8 hours, the employee is entitled to (a) two 10-minute paid rest breaks; and (b) one 30-minute meal break” plus one 10 minute paid rest break for any additional two hours…

Does that sound like dry, boring legal language, and isn’t what is stated here a no brainer anyway? Sure, but many would be surprised how often Employment Relations Act 69DZ and similar acts in OECD countries get violated or distorted. Ok, but isn’t that a purely legal or political issue and has nothing to do with art? Well, hang on…

Based on his personal experience as a worker in a potato chip plant and his friendship with migrant workers from Oceania, John Vea’s new assembly of his works Employment Relations Act 69DZ (2019) and Import/Export (2008-2016) at Auckland’s Gus Fisher Gallery “prefaces the voices and lived experiences of migrant workers from a Pacific perspective.”(1) Vea’s perspective on current mechanisms of capitalist exploitation, which becomes even more topical due to the recent political announcements of the newly elected government regarding seasonal labour, is complemented by Jasmine Togo-Brisby’s work in terms of the longue duree, the long-term historical aspects of colonial exploitation.

Together Togo-Brisby and Vea explore various facets (aesthetic, historical and political) of slave-labour, indenture and modern forms of minimum wage economies and migrant labour in the South Pacific and beyond. Their show Outcast is political art, but in the best possible sense: it is first and foremost art, it works with concepts and feelings of surprise, beauty, even wonder but also of sadness, anger, critique and frustration. It shows, it does tell; it is not demagogical or agitprop, yet it is based on a discernable and clear standpoint: respect for and solidarity with those politically often neglected casual workers who are the backbone of some of New Zealand’s most profitable export industries.

Their joint presentation includes Vea’s installation of a typical farm labourers’ smoko. On display are cheap plastic chairs, a large plastic dining table, a microwave and a fridge on whose door there is a handwritten list of the telephone country codes of Samoa, Tonga, Vanuatu, Fiji and other Pacific regions from where the majority of New Zealand’s seasonal labourers originate. On the walls the visitor can see photographs of tropical beaches, both evocative and clichéd. The installation recreates a feel of desolation and homesickness but also of subtle camaraderie and solidarity, as the table, although simple, is large and capable of holding a communal meal and a game of cards.

What at first glance appears to be a pragmatically spartan and artless space, becomes transparent not only of the labourers’ plight and melancholy, but also their dreams and aspirations. As well as forms of political resistance, as the thoughts and daydreams of the migrant workers seem to hover in the room. Some find poetic and political expression in the quotes that are inscribed on the photographic posters. A good example would be a passage from Teresia Teaiwa who contemplates the everyday toil of the workers against the backdrop of the Pacific Ocean’s eternal grandeur, both as an intricately familiar and a detached sublime space:

“We sweat and cry salt water so we know that the ocean is really in our blood.”

Or consider Albert Wendt’s statement which explores questions of cultural and spiritual identity against the backdrop of an island photograph, questions that concern the everyday and profane as much as the metaphysical. The latter being often, and wrongly, associated with ‘high art’ and academic discourses only, but not with agricultural labourers. As Wendt says:

- “In our various groping ways, we are all in search of … heaven, that Hawaiki, where our hearts will find meaning; most of us never find it, or at the moment of finding, fail to recognise it. At this stage in my life, I have found it in Oceania: it is a return to where I was born, or, put another way, it is a search for where I was born.”

On seeing the installation and reading the quotes, I found that they triggered a whole trail of personal experiences and thoughts (and I think it the hallmark of good art exhibitions that they challenge the viewer to relate personally and with recalling their own collective cultural background(s) to the art). So, at this stage, allow me a digression into some of my own personal politics, if you like, and then return to the art work of the exhibition.

On studying Togo-Brisby’s comments on the exhibition, I noticed that some of her whanau who came from Vanuatu were house slaves at the Wunderlich’s family home in Australia.(2) Having been born and raised in Germany, this Central European connection drew my attention. After a bit of research I came across about what, at face value, looked like a typical Anglo-German colonial ‘success story’ (the kind of story that during my childhood and youth was still widely considered aspirational for Pakeha males).

Through hard work and capitalist strategising, the Wunderlichs created a multi-national industrial empire that included the fabrication of pressed metal ceilings, tiles and asbestos based building materials.(3) Iconic Australian buildings such as the Sydney Town Hall were fitted with Wunderlich ceilings and, through an office and distribution centre in Wellington, the Wunderlichs also exported to New Zealand. Some of their ceilings are still around in my home town Hamilton, in the historical Greenslade House for instance, that resembles a European castle overlooking the Waikato awa.

Alfred Wunderlich (1865-1966) and his two older brothers Ernst Julius (1859-1945), and Frederick Otto (1861-1951) soon became members of the Australian political and cultural establishment, partly disrupted by the two World Wars during which they positioned themselves as loyal Australian citizens and kept a low political profile and a high financial balance. When Alfred died at the age of 101 he could look back at a life which saw the brothers being educated and trained in Europe, doing business with and in Germany and France as well as South Africa, Australia, the Dutch East Indies and New Zealand, streamlining the manufacturing processes of their often jointly owned companies and paternalistically improving health and social standards for workers and administrators, all the while discriminating against Catholic employees (4), and generally relying on supplies produced by cheap labour, including poor European immigrants and workers who had come to Australia as a result of ruthless ‘blackbirding’.

Having a fine bass voice, Alfred sang in a Sydney choir, became the chairperson of the Royal Philharmonic Society of Sydney; an original composition (String Quartett #2) was dedicated to his equally music-loving brother Ernest by a renowned composer friend, the Australian-New Zealand composer Alfred Hill. In 1934 Alfred was appointed Chevalier of the Légion d’honneur for his work with the Sydney Alliance Française. And so the Wunderlich story went on.

The family history of the Wunderlichs, some of whose members were social and technological innovators as well as patrons of the arts and at the same time hugely exploitative, is well documented. Like many other members of their social and cultural circles they were ‘global players’, a group of international capitalists who, under slightly different circumstances, still exist and call the financial shots today.

But what do we know about the workers who were coerced or tricked into leaving their island homes in order to work in Australian or New Zealand factories, farms or as the Wunderlichs’ house slaves? What do we know about their biographies and their dreams? Next to nothing. Outcast makes us aware that not only the economic foundations but also the history of ‘Western’ (including Australian and New Zealand) ‘high culture’ to a large extent rests on the forgotten lives and travails of a vast group of exploited labourers whose stories have never been recorded.

Together with a critique of the often complex issues of colonial politics and exploitation, the exhibition raises the question what true democratic culture, in politics, in education, but also in the arts, may look like. In some former Eastern Bloc countries in Europe, the Communist Party encouraged the workers to create their own works of art. But the poetry workshops and painting classes were soon stopped, when the workers in their artwork took issue with their corrupt, usually male party bosses who deviced their own forms of exploitation.

Still largely male dominated, political power and excessive profit making have become the dominant and, in politics and the academe, often only rhetorically challenged fundamental principle of global civilisation. These days, the ideology of neo-liberal capitalism has been elevated to the status of an ersatz-religion, a huge international dance around the ‘Golden Calf’ of consumerism, peer pressure, status symbols and profit. Some of the borrowed metaphors of the global capitalist system: the supposedly guiding ‘invisible hand’ (Adam Smith) of the market, or the ‘shopping paradise’ are directly coopted from religious traditions. When recently challenged about his policy of austerity and the hardship created by inflation, the German Finance Minister Christian Lindner responded with his ‘belief; in the ‘higher wisdom’ (‘höhere Weisheit’) of the market.(5)

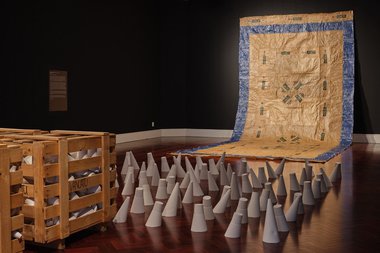

The link between false religion and exploitation is directly visible at the exhibition. In the gallery’s large exhibition hall there is an installation that is reminiscent of a sacred space. As in a church nave, it directs the visitor’s view to a central illuminated area at the end of the room which looks distantly like a choir or altar room. A curtain or tapestry made of sugar sacks rises from the floor and shows a tilted cross composed up of company logos. It is an adaptation of Ni-Vanuatu barkcloths or nemasitse which Togo-Brisby employs to explore and critique forms of capitalist work ethics (which, as Max Weber pointed out, are rooted in religious traditions e.g. ‘Protestant work ethic’(6)) but also value creation, branding and the veneration of money.

In the space in front of the cloth there are large boxes made from simple wooden slats containing plaster cones. These cones look like stylised sugar canes—or even people. Togo-Brisby also has plaster forms (of tam-tam drumming figures) in the domed entrance hall of the Gus Fisher Gallery, but that work had to be removed because it had been partially damaged in an accident. Through these symbolic and evocative objects and their arrangements, a wide South Pacific horizon of material, social and political history unfolds in front of the visitors.

In conclusion, this exhibition, which initially may seem a bit prosaic and obscure, offers a wide range of aesthetic and intellectual gains for everyone who is prepared to engage with the objects and with the narratives and contexts of which they are a part. The installations are redolent of human labour and dreams, and they are thought provoking. As the exhibition brochure says: “Shaped by the artists’ own histories and experiences, Outcast reflects a process of talanoa where each artwork is part of a shared story of ideas and encounters.”(7) Visitors are invited to enter the dialogue; and many leave the exhibition with new, or renewed, political insights.

Norman Franke

(1) https://gusfishergallery.auckland.ac.nz/outcast/

(2) https://gusfishergallery.auckland.ac.nz/outcast/ and also: https://www.pagegalleries.co.nz/exhibitions/107-jasmine-togo-brisby-dear-mrs-wunderlich/overview/

(3) Biographical information about the three Wunderlich brothers Alfred, Ernst Julius and Friedrich (Frederick) Otto with the context of Australian Victorian and Edwardian colonialism can be found here: https://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/wunderlich-alfred-9295

(4) https://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/wunderlich-ernest-julius-9204

(6) Martin Luther King Jr. succinctly critiqued an affirmative reading of the ‘Protestant work ethic’ in modernity: “We have deluded ourselves into believing the myth that capitalism grew and prospered out of the Protestant ethic of hard work and sacrifice. The fact is that capitalism was built on the exploitation and suffering of black slaves and continues to thrive on the exploitation of the poor-both black and white, here and abroad.” https://theworld.org/stories/2017-12-04/smiley-capitalism-has-always-been-built-back-poor-both-black-and-white

(7) https://gusfishergallery.auckland.ac.nz/outcast/

[For the public record, this show has been beset by unfortunate exhibiting problems: the presentation time was suddenly shortened (ie. closed) due to the removal of trace fibres of asbestos from the exterior—an irony considering the Wunderlich history—and the Jasmine Togo-Brisby exhibit, Hold, was withdawn due to accidental partial damage by a visitor (as mentioned). Ed.]

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.