John Hurrell – 16 December, 2016

In his notes on the back of the canvases, where he lists the music he listened to during each work's execution and the types of gestural vector he made, Raine calls himself ‘Baron Yeti' - after the clothing company with a brand logo that shows a person inside an abominable snowman suit. We see them peeking out through the mouth. In other words, he seems to be saying: don't trust exteriors . ie. Raine's external behaviour, the wild intoxicated painting, is just an act.

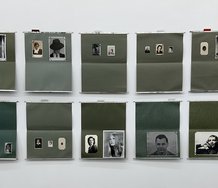

Inside the large rectangular gallery of the Gus Fisher Toby Raine presents sixteen oil paintings as an installation (for a doctorate) that exploits the floor space. On one narrow wall by the two entrances is a single unframed stretcher, and down the opposite end are five others - high up near the ceiling. In parallel lines marching down the centre of the room are two sets of five, the painted canvases held high in the air by what seem to be modified music stands, except they are screwed to the bottom struts of the wooden stretchers.

With each artwork one side has a painted on printed text, the other a sort of mutilated, partially erased portrait, a drippy and loosely gestural angular hybrid blending Frank Auerbach with Franz Kline. Both recto and verso planes seem crucial components to each work. Facing the entrances are the written titles and procedural footnotes, while facing the other end with its five works on the wall are the frenetic portraits, all of bearded men, and all with their physiognomies disrupted by energetic slashes of straight lines, joined at acute angles.

The theatricality of Raine’s display is accentuated by the pervading aroma of oil paint and the presence at the far end of a filthy blue-grey corduroy drop cloth, on which are positioned scattered soiled rags, photocopies of various bearded gentlemen (that include some rock stars and writers, the artist, other artists, an actor playing Jesus, and the once hirsute lecturer Allan Smith), rolls of canvas and a forlorn pair of encrusted slippers. Plonked in the middle of the tatty detritus is a sort of greasy shrine or grey-green altar, presenting at eye level various caked paint receptacles, surrounding a small model ram’s head with horns. It all has a definite Baconseque ambience, but with overtones that seem to mock believers - those male heroes who adore daubing and ‘spraying’, that represent a certain sort of masculinist cliché.

Raine claims in the gallery blurb that all this is intended to be ironic, but of course we have no obligation to take his word for it, and you could argue the other way - that no humour is intended. We need to find clues in the work if we are to be convinced that he is not as deliriously fond of oil paint (as a malleable sticky substance) as he seems - and that that infantile ‘faecal’ play is not the driving (sole) motivation for his practice. That there is a systematic, overarching thought process involved.

In his notes on the back of the canvases, where he lists the music he listened to during each work’s execution and the types of gestural vector he made, Raine calls himself ‘Baron Yeti’ - after the clothing company with a brand logo that shows a person inside an abominable snowman suit. We see them peeking out through the mouth. In other words, he seems to be saying: don’t trust exteriors . ie. Raine’s external behaviour, the wild intoxicated painting, is just an act. He is claiming here it is a contrivance - but is that believable?

So what of the title: ManCrush? Is it about homosexuality, is it about attacking a strident masculinity, or is it about his spatial compression of male faces? It is a clever word combination that is extremely evocative. So varied in its associations.

And what of the fixation on beards and the ‘lumberjack look’? Are the hairy faces merely a cipher for rugged male virility or is it a formal thing; a facial quality that is easier to have as a tonal foil for the violent diagonals? The presence on the floor of a reproduction of Courbet’s The Origin of the World is loaded too. Is the faceless woman’s vulva a reference to vagina dentata, dread of the female ‘castrating’ organ, a fear of women’s power? Is the artist’s putative interest in homosexuality a consequence of that, a retreat into the arms of men?

With Raine’s very directional installation one wonders what would happen if the ten freestanding paintings on the floor were flipped around so that the texts faced the altar, the line-blocked faces the doors, and wall works presented only the printed working notes - their precise language describing his manual actions, musical instigators, canvas turnings and general production ethos. It would accentuate the position of painter as writer, not as mark or shape producer. He could be like Lawrence Weiner and not need to make the work at all. The description would suffice.

In the published catalogue essay written by Julian McKinnon, Raine gets a little huffy at being called a portrait painter, but most people would say that he is. However if we remember Robert Rauschenberg’s famous 1961 telegram, “This is a portrait of Iris Clert if I say so,” then Raine has a point. Anything can be a portrait if the artist declares that intention to be the case - and that status can be reversed too. In 1963 Robert Morris took this idea further by ‘negating’ the aesthetic qualities and content of an earlier artwork (Litanies) by making a public statement (Document) with a notary because the collector who possessed it was slow in paying, so Raine would be perfectly free to legally determine the generic /ontological status of his practice by ‘withdrawing’ its portrait attributes if he so wished.

If Raine went that far and saw himself as a conceptual artist then it is likely he would have a problem with the physical traces, which the above scenarios ignore if he is genuinely conflicted. He could physically scour the very beautiful painted obliterations by grinding down the impasto texture and covering it with matt black paint so that the text on the other side became the sole provider of information. That is if he genuinely felt being called a portraitist was total anathema, and he didn’t want to acknowledge he gets (or gives) pleasure from shifting oil paint around on a support.

In 1967 Art & Language member Mel Ramsden (he joined in 1970) made a Secret Painting with black paint covering a previously painted surface, where he stated “the content of this painting is invisible; the character and dimension of the content are to be kept permanently secret, known only to the artist.” To this Raine appears quite different. He doesn’t want secrecy, nor does he seem desirous of having text as a substitute, though his presentation partially implies it. He speaks (to McKinnon) of obsessively making paintings that ‘work’.

“I’m a painter. I’m making paintings. It’s not about images or conceptual languages. I’m only interested in paint as the final result, as a physical thing.”

Yet this is obviously not so. His practice is all about images and conceptual languages. They are embedded in his act of painting and his act of installing them. For if he were only interested in paint, he would eschew writing out textual description, or planning the positioning of elements in a theatrical hang.

This is a case of trust the art, not the artist. The work is complex and contradictory with a perverse logic being played out that is not only about painterly substance and the real and illusionistic spaces it can create - pertaining to mutilated faces that once referenced a certain kind of desirable masculinity - but also about energising (but contemplative) ritual and fakery that in the name of satire unpicks and dismantles it.

John Hurrell

Recent Comments

John Hurrell

That is so funny. I should have thought of the anagram thing. Yet the Baron Yeti logo is an amazingly ...

Toby Raine

Yes I heard something about that. A face to face critical discussion would be interesting, though obviously it would require ...

John Hurrell

Thanks for your nice letter, Toby, and for introducing me to some urban slang I hadn't come across before. I ...

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column

This Discussion has 4 comments.

Comment

Toby Raine, 2:43 p.m. 11 January, 2017 #

Thanks for the review John. You have given it good thought and made many valid observations, most of which I would not argue with. The one exception, perhaps, would be the points about homosexual connotations - Man Crush is a well known bit of urban slang, defined online as when a straight man has a kind of crush on another man, not sexual, but more like having a hero or role model. That said, it is inevitable that when using such a term it will attract this sort of speculation, regardless. This makes it more fun, I suppose.

I don't debate your other points because they're correct. It's obvious I'm obsessed with moving paint around on canvas. I imagine anyone in my position would agree that never was there a more likely situation to open oneself to self-contradiction and debate than spending four years academically articulating your own contribution to this wonderful yet totally problematic medium.

I think the Gus Fisher show, in terms of being a summative point of inquiry, was an epithany that the problematic and the wonderful need to be embraced at the same time (at least in my case) for the act to continue.

But really, what a frustrating thing to try and talk about - ways and reasons for a painting practice. I'm glad, in terms of study, that this chapter has concluded.

Thanks again for the great review.

Toby Raine.

John Hurrell, 5:44 p.m. 11 January, 2017 #

Thanks for your nice letter, Toby, and for introducing me to some urban slang I hadn't come across before. I did hear your show (title and presentation) got people talking, some even angry. Hopefully you got some constructive dialogue in the end - face to face.

Toby Raine, 9:04 p.m. 11 January, 2017 #

Yes I heard something about that. A face to face critical discussion would be interesting, though obviously it would require those individuals' willingness to extend their opinions outside of private Facebook pages.

I should clarify one more thing while we're talking, John. Baron Yeti has nothing to do with a clothing label - I was unaware one exists. Baron Yeti is actually an anagram for Toby Raine that I discovered six years ago (painting alter ego if you like - very much tongue in cheek..).

See you around the usual art haunts. Toby.

John Hurrell, 9:11 a.m. 12 January, 2017 #

That is so funny. I should have thought of the anagram thing. Yet the Baron Yeti logo is an amazingly apt coincidence. https://www.streetartsf.com/baron-yeti/

Delicious chance!

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.