Andrew Paul Wood – 23 November, 2017

Although I don't sense quite the fiery intensity of passion in the discourse now that there was then, it's a dichotomy that threads all the way through the book in one form or another. It's probably the most important dialogue in the last century of New Zealand art, if not the only important one.

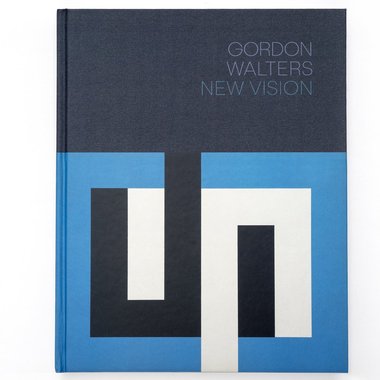

Gordon Walters: New Vision

Three essays by exhibition curators Lucy Hammonds, Julia Waite and Lawrence Simmonds, plus five others from Deidre Brown, Peter Brunt, Luke Smythe, Rex Butler and ADS Donaldson, and Thomas Crow.

Commissioning editor Zara Stanhope.

Design: Neil Pardington

Hardback, 240pp, coloured illustrations, 300 x 240 mm

Published by the Dunedin Public Art Gallery in partnership with Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki, 2017

Observe the young and tender frond

of this punga: shaped and curved

like the scroll of a fiddle: fit instrument

to play archaic tunes.

I see

the shape of a coiled spring.

- “Conversation in the Bush”, ARD Fairburn

It’s not often that a book makes you catch your breath before you even open it, but Gordon Walters: New Vision (Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki and Dunedin Public Art Gallery, 2017) is such a book, the publication accompanying the survey exhibition of the same name. The design is absolutely exquisite, refined, perfectly judged and weighted, outside and in, in every respect; fonts chaste as a Vestal (though ‘o’s and ‘a’s are at times hard to tell apart with tired eyes), and extravagantly illustrated. Walters would, I think, have approved. It complements his own pared-back modernist sensibilities so well. I was concerned that the rapture induced by such a truly beautiful book might make it difficult to be objective about the actual content.

A quarter of a century has passed, and with it, perhaps, a cooling of tempers, since the Headlands controversy in 1992 in which Rangihīroa Panoho excoriated Walters (Walters, at the time, seventy-three, two years from death, and frail) in the catalogue essay “Maori: At the Centre, On the Margins”, for what he perceived as shameless cultural appropriation of Māori koru and pītau forms. That’s certainly a legitimate and not unexpected reading of that phase of Walters’ career, though at the time it did seem odd to contrast Walters’ “bad” appropriation with Theo Schoon’s “good” collaboration, when Walters was more interested in formal properties of circles and rods à la Auguste Herbin than any nationalist mythmaking or imposition of meaning (Francis Pound once made the comparison to Barnett Newman’s “zips”), while Schoon was quite brazenly out to take, and reinvent with a Bauhaus blut transfusion a traditional Māori visual culture he saw as moribund based on his assumptions of cultural knowledge.

Panoho’s justifiable, if overly zealous (given Walters’ age) observations caused a mephitic stink in our very small art world pond, and Pound retaliated two years later with his book The Space Between: Pakeha use of Maori motifs in modernist New Zealand art, determined to reframe Walters as the herald and prototype of official biculturalism (a cumbrous monolith at the best of times). This view is certainly not without its merits, but Pound wasn’t prepared to give any ground to the idea that there could be more than one nuanced reading of the situation and that Panoho had an entirely reasonable point. Although I don’t sense quite the fiery intensity of passion in the discourse now that there was then, it’s a dichotomy that threads all the way through the book in one form or another. It’s probably the most important dialogue in the last century of New Zealand art, if not the only important one— no less relevant now, given discussions around younger artists, like Francis Upritchard and Rohan Wealleans, for example.

DPAG curator Lucy Hammonds does a wonderful job of encapsulating Walters’ early development—easily a book or two’s task—teasing out influences, particularly the influence of Theo Schoon, though illustrated examples of Schoon’s work in the text are noticeably few. This doesn’t make much sense given his influence in what was effectively New Zealand’s equivalent of the Picasso-Braque friendship. One might have reasonably expected the inclusion of the circa 1942 photograph taken by Schoon of him, Walters, and Denis Knight Turner in the basement of the Wellington YMCA, but no. I am conscious that even acknowledging my personal bias as a Schoon scholar (my MA thesis gets a hat tip in the bibliography) it seems peculiar he’s so absent visually. If anything, there should have been an essay dedicated to that by itself. How else did Walters know to seek out the relatively obscure artist and designer Wally Elenbass in Rotterdam, whom Schoon would have known or known of from Elenbass’ teaching at the Academy when Schoon was a student?

The theme of influence (and the anxiety thereof—a perennial theme for any study of Walters’ work) is continued in Auckland Art Gallery curator Julia Waite’s essay, “New Networks and a Paper Museum”. Really it’s two or possibly three essays squished together, because while it tries to build a series of connections between Walters’ scrapbooks and notebooks of indigenous sources, MoMA founding director Alfred Barr’s systematic genealogy of modernism, and Walters’ interest in Mondrian and Neoplasticism (sans the theosophic-anthrosophic mysticism)—and this to some degree succeeds— on the whole it feels like a forced and inelegant exercise in shoehorning without a clear purpose.

Any attempt to read Walters into an international modernist movement is always problematic. Most of his understanding of those broader trends were always second or third hand, through books and magazines, or mediated by people like Schoon who filtered it through their own concerns and agendas. “Distance,” as Charles Brasch wrote, “looks our way”, but never more quizzically than as it does at our artists. Even when Walters travelled to Europe in 1959, he was looking at mainly the past glories of the previous generation (Mondrian died in ‘44), and the increasingly provincial dead ends of the Schools of Paris and Rome. Modern art’s magnetic pole had well and truly relocated itself to New York by then.

I’m not actually entirely sure of the purpose of Laurence Simmons’ essay, beyond the curatorial acknowledgement; an impressionistic, and at times opaque recapitulation of what is covered in greater detail in the other essays with some philosophical flourishes, but not adding much beyond a salient, and all too short, foray into the influence on Walters of Chinese art and culture. This manifests through Georges Duthuit’s Chinese Mysticism and Modern Art (1936) and his relationship with Chinese-Australian artist’s model Dorothy Henry in Sydney in the late 1940s, and also through Schoon, who was fascinated by Chinese aesthetics and was familiar with the Chinese community in Indonesia and holdings in Dutch museums. Neither Simmons, nor any of the other contributors, have picked up on Walters’ exposure to modernism’s take on African art through Carl Einstein’s Negerplastik (1920) which Schoon owned a copy of and translated aloud for Walters. Still, Simmons’ text has its aesthetic pleasures and tickles the brain, though it would probably have been better positioned as a summary at the end of the book.

What might have been more interesting (and better suited to Simmons’ intertextual expertise) would have been an examination of Walters influence on the artists who emerged in the 1990s—here I am thinking of Peter Robinson’s jet plane forms (circa 1994), Shane Cotton’s Picture Painting (1994) which pays homage to (or critiques) Walters’ 1944 Chrysanthemum, hybridising it with the pot plants found in the Rongopai painted tukutuku, Cotton’s reverse appropriation of Australian painter Imants Tillers’ appropriation of Walters’ appropriation of pītau (it all gets pretty recursive and tangled), and Michael Parekowhai’s playful Duchampian take on Walters in Kiss the Baby Goodbye (1994).

What is it with 1994? Is it a coincidence that all this activity seems to coincide with the publication of Pound’s The Space Between that year, fermenting and fomenting away since Headlands? Te Toi Hou, Elam’s Māori Art Department, with Selwyn Muru and Kura Te Waru Rewiri, was established that year as well. 1994 also saw Auckland Art Gallery put on the decidedly Pākehā affair, the William McAloon-curated Parallel Lines: Gordon Walters in Context, which would have got up multiple noses.

The estimable Deidre Brown takes us back to the central issue of Walters’ career and all of modern New Zealand art, appropriation and the relationship between Pākehā modernism and Te Ao Māori. Although Brown is at all times diplomatic, one comes away with the unavoidable impression that she is decidedly in the Panoho camp regarding Walters’ original sin, regardless of what he may have thought he was doing, and some of her interpretation of his own words comes, at least in my opinion, dangerously close to bad faith reading, such as:

“Walters felt differently [than Schoon], observing later in life that: ‘Theo invested considerable energy in growing and decorating his own gourds and in painting kowhaiwhai patterns in a largely traditional way. I was out of sympathy with this approach and felt that he was trying to bring back the past.’ His comment is revealing, suggesting a strongly held conviction that the role of the contemporary (Pākehā) artist was to sample and extend derived ideas, not to invest in their perpetuation.” (p107)

I’m not convinced that’s what Walters meant at all. In fact, it appears as though he is merely stating his own individual preference (he wasn’t any kind of proselytiser or polemicist), and his tone is far from suggesting “a strongly held conviction” about anything beyond modernist teleology. Nonetheless Brown gives fair coverage to Walters’ Māori defenders (apologists?) as collected by Pound in The Space Between—Arnold Manaaki Wilson, Para Matchitt, Hirini (Sydney) Moko Mead and Cliff Whiting—and later supportive comments by Jonathan Mane-Wheoki, emphasising that it isn’t a clear-cut situation, or at least not generationally (I get the impression that an even younger generation of Māori artists are even more sanguine about it, as though a reciprocal utu had struck a kind of uneasy equilibrium). This section of the essay concludes on a strange note:

“Eventually the main protagonists in the debate, [Ngahuia] Te Awekatuku and Panoho on one side and Pound on the other, moved on to other intellectual concerns and the appropriation debate faded away from academic art history. It remained, however, very much alive for other Māori.” (p112)

Faded away? Not that I’ve noticed. Postcolonial (or as I prefer to call it, “Late Colonial”, because we’re still living it) theory and discourse around appropriation have stayed front and centre in New Zealand art discourse. You can’t move for Fanon, Spivak and Bhabha. Indeed, as Robert Leonard points out in his essay “Gordon Walters: Form Becomes Sign” (Art and Australia vol 44, no 2, 2006) a decade ago, Walters’ “koru” paintings are so weighted down with appropriation discourse, it “has blinded New Zealand audiences to the way they operate as paintings, their formal-phenomenological concerns.” Walters is unavoidable in any discussion of New Zealand art, and the issue of appropriation is unavoidable in any discussion of Walters.

Which is why I’m surprised that Brown shifts focus to graphic design and logos from the 1980s and ‘90s without addressing the irony-infused responses of artists like Cotton and Parekowhai. On the other hand, Brown importantly highlights the 1991 claim brought before the Waitangi Tribunal against commercial usage of the Walters “koru” by six iwi claimants (Wai 262) on grounds of theft of Māori intellectual and cultural property, which went about as well as you would imagine when ruled on in 2011. Wai 262 did, however, highlight the lack of protections for Māori visual culture from commercial exploitation and the inability to distinguish between offensive and positive commercial usage. Expert testimonial from artist and graphic designer Jacob Scott (Ngāti Kahungunu and son of architect John Scott) and Michael Smythe on behalf of the Designers Institute of New Zealand, absolved Walters’ legacy of ethical wrongdoing.

And a minor cavil: in the end notes of Brown’s essay, Theo Schoon’s 1985 article in New Zealand Potter, “My Work with Plaster Stamps,” is unrecognisably cited as “Work with Postage Stamps”, but that’s what you get when you cite second-hand from Pound’s The Space Between without checking.

Peter Brunt’s essay on the influence of Pacific and Oceanic art on Walters is exemplary. The arguments are tight, and it introduces a lot of new material, or at least material new to me. Seeing how a 1958 Walters collage relates to Marquesan bowl patterns is revelatory, but it would have been helpful to note that, as in many cases, these prototypes are filtered through the aesthetics of the Italian modernist painter Giuseppe Capogrossi, as Simmons points out.

The Australians have always better at understanding what their artists got up to in Europe than New Zealand art historians are about our own. I was immediately intrigued to see Aussie big guns Rex Butler and ADS Donaldson wheeled out, and not disappointed. After a relatively light glossing of Walters’ time over the ditch (I would have liked more, and Walters’ interest in Aboriginal art especially), we get down to some truly ground-breaking stuff in Paris. I am completely convinced by the connection they make to the French geometric abstract painter Edgard Pillet, and putting works by the two artists from the early 1950s side by side, were either alive today, Pillet would have ample grounds to sue for plagiarism. That again raises the issue of appropriation in Walters’ process, as in his use of mental patient Rolfe Hattaway’s drawings (acquired via Schoon), but in the case of the Pillet-esque works there are no fig leaves to hide behind.

Art historian Luke Smythe contributes a short, pithy assay of Walters’ relationship to European abstraction, picking up the loose threads of the standard version that didn’t otherwise make their way into the other essays, but nonetheless need restating. I’m not sure, however, about the piece by American art historian Thomas Crow on Walters’ relationship to hard edge painting. Yes, that’s visually obvious, but again it’s very much at second-hand via time spent in libraries—he was particularly interested in Californian artist John McLaughlin—and the connection to Bridget Riley is superficial (Victor Vasarely would be a more natural fit, but even then it’s only of slight import), although he was interested in Riley’s work, travelling to the touring exhibition of her work that travelled to Australia in the 1970s. One gets the impression, much like Walters’ knowledge of American art, that Crow was largely working from the pictures.

This is a superlative volume. All my plaintive little niggles and moans aside, if you were going to buy one expensive art book this year, make it this one (even if you only ever look at the pictures) or Undreamed Of… 50 Years of the Frances Hodgkins Fellowship (Otago University Press, 2017) by Priscilla Pitts and Andrea Hotere.

Andrew Paul Wood

Recent Comments

jim barr

Andrew is right in saying Gordon Walters would have loved the elegant design this book. But it is a little ...

Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

This Discussion has 1 comment.

Comment

jim barr, 5:57 p.m. 25 November, 2017 #

Andrew is right in saying Gordon Walters would have loved the elegant design this book. But it is a little harsh to claim he was frail when 'Headlands' was shown in Sydney and in the following months as the Panoho backlash and fuss over Robert Leonard’s including him in the section ‘Inside Out’ raged. From my memory it would be fair to say that although Gordon didn’t love the fighting over his head, he was pretty unfazed by it. And, missing from the very male line up of influences, (apart from two of the briefest mentions) is Sophie Tauber-Arp who Walters often mentioned and admired.

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.